“What is your biggest author dream?” somebody asked.

“Cosplayers,” I said. “I want to see people dressed up like my characters.” See, I’d put a lot of thought into the clothing in Black Sails to Sunward, and I thought it would be really cool to see it in real life.

But I got impatient, so I decided the best thing was to be the cosplayer I wanted to see in the world.

In the Mars of my books, fashion is having a bit of a throwback. As society became more stratified and traditional, people started cosplaying the past. This is pretty universal for fascist societies–first they idealize the past, then they try to live it. So, while my decision to dress my futuristic sailors in historical costumes was partly based on my deep and abiding love for a frock coat, I also felt it made a certain amount of sense.

In Their Majesty’s Navy, clothing is even more important. Dramatic, formal uniforms allow the officers to present a certain kind of prestige that impresses both the spacers and their enemies. Outsiders find Martians a bit over-the-top, especially Martian nobles, but even they have to admit the stunt kind of works:

“There’s shit you do that’s utterly ridiculous, it’s like a godawful period piece, but if the fairytale works, who am I to judge? That boy indoors thinks he’s a prince, and you know what? That makes him one. Because he believes it and he’s got you all believing it, and it’s a spell that’s forcing Earth to believe it.”

from book 2, The Sea of Clouds

The main difference between Martian clothing and historical clothing is gender. While Martians do still have a concept of gendered clothing, it’s not unusual for all genders to wear menswear for daytime and gowns for evening events. There are strict rules about when you can wear a white coat and when you must wear gloves, but you can wear clothing of any gender so long as you look absolutely smashing while doing it. Lucy, my main character, strongly prefers menswear for any but the most formal occasion.

Lucy has a particular obsession with clothes. One she hasn’t been able to satisfy much in recent years, as her family has fallen on hard times. So it’s no wonder she develops such a fervent attachment to her Navy uniform. It’s beautiful, it’s dignified, it cost a lot of money she couldn’t easily afford. When her shirts come back from the laundry overnight, she’s pleased. When she gets blood on her uniform, she fights off tears. It’s everything to her, symbolizing her duty and honor–which, as the book goes on, get just as tattered as her beautiful Navy coat.

Anyway, I set out to make the costume exactly as described in the book. I was not going to try to be Lucy–Lucy is apple-shaped, and I am more box-shaped. I’m also not blond anymore. I just wanted the costume, so I set to work.

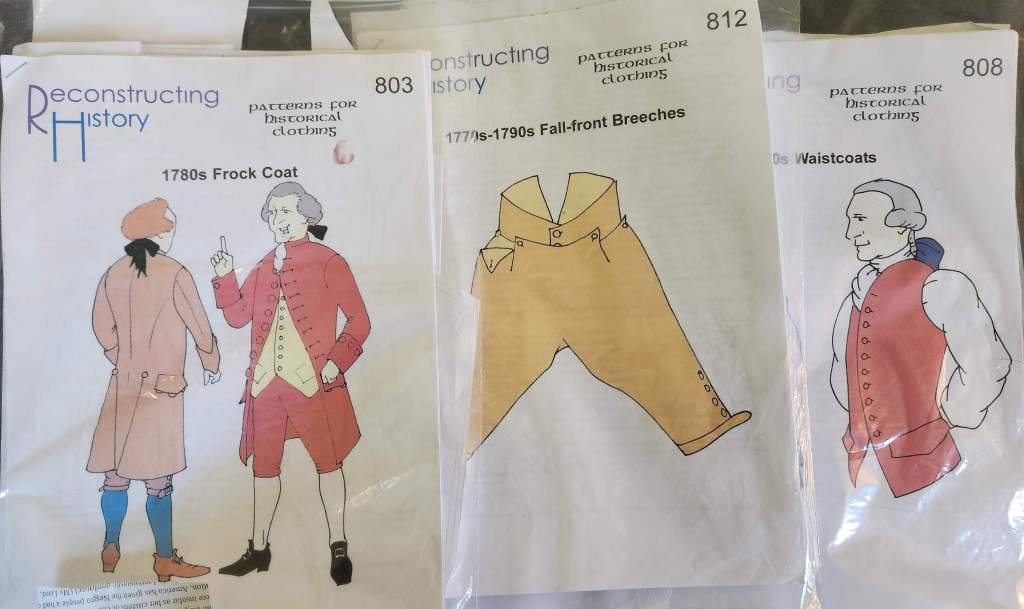

The patterns (except for the shirt, which I drafted myself from basic rectangles) I got from Reconstructing History. I can’t honestly recommend them; the instructions were useless and I had to resize absolutely everything because even the largest size was a tent on me.

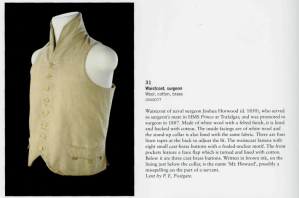

The shirt was made of fine handkerchief-weight linen, the waistcoat and breeches of canvas twill, and the coat of wool. Mars, even terraformed, is never going to be very warm. I thought flax, hemp, and wool might grow there better than cotton. Canvas twill in particular was also popular with both sailors and soldiers during the 18th and 19th centuries. It’s a heavy, hard-wearing fabric which would hold up well to Lucy’s stunts. And it’s also breathable and washable, a handy feature when you’ve got forty people stuck in a tin can and the washing machine runs on a hand crank.

I altered the patterns significantly to match what I had seen in historical reference photos. The “uniform” of the British Royal Navy in the late 18th and early 19th century was not so formalized as uniforms are today. Instead of being issued your uniform, you’d have your tailor make a fairly standard gentleman’s suit, with specific details in color and trim decided by the Navy.

The whole project took months. I’m not even entirely sure when I started. Every stitch was done by hand, partly for authenticity but mainly because I can’t be bothered to take out my sewing machine. I sewed while watching TV or listening to Simon Vance read the Master and Commander books. (Topical! Jack Aubrey, stop ruining your clothes all the time, I think Killick might literally cut you.)

First, the shirt. Men’s shirts of the time pulled over rather than buttoning down. They were essentially an undergarment–the material was thin and you’d never appear in public without a jacket.

Next, the waistcoat. This covers up the parts of the shirt that show, except for any neck ruffles you might have. There’s a handy pocket for your watch.

The breeches were the most difficult part. During the late 18th century, fall fronts were in. Instead of a fly, the whole front of the trousers flaps down when you need to pee. I puzzled a while over whether Lucy would actually want this feature. But then I remembered that, in space, toilets involve a suction hose. It seemed convenient to keep the flap for everybody.

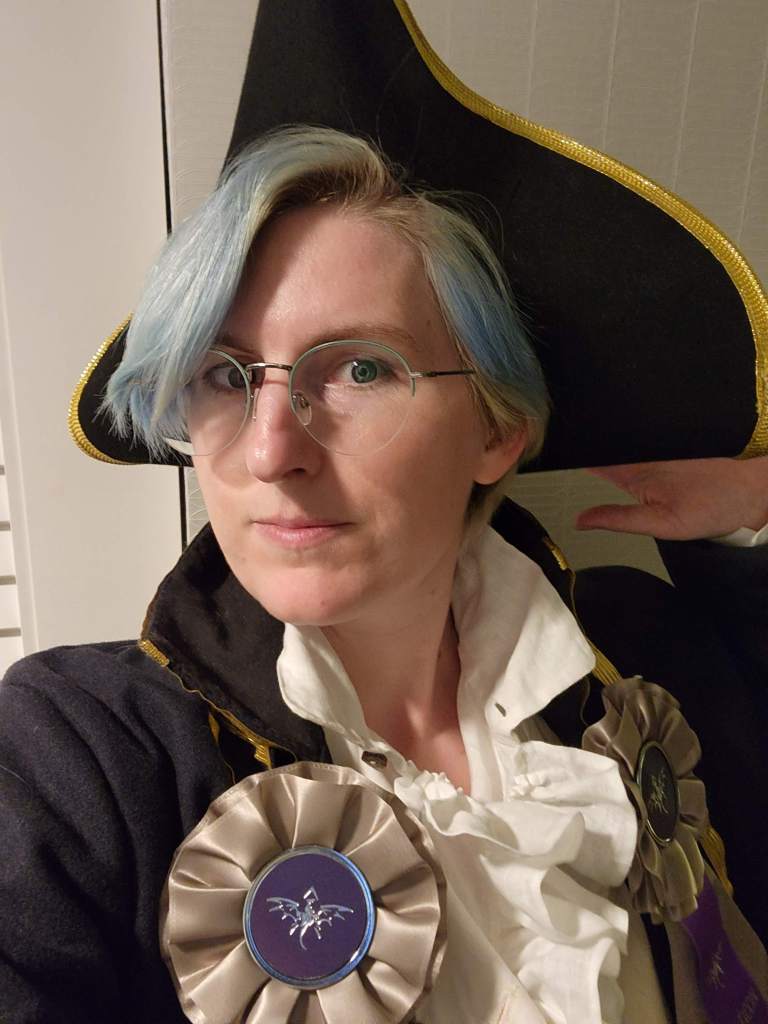

Lastly, the coat. The amount of gold braid and buttons was a hint to your rank. While I don’t have any pictures of extant midshipmen’s coats–I believe midshipmen would keep the same coat after promotion and just add more bling–I thought it made sense to use a bit less gold braid than I saw in the captains’ coats. I also omitted epaulets. The rules in the real Navy changed over the years, but I standardized them for my Navy: one epaulet for lieutenants, two for captains. Lucy, as a midshipman, has none.

The traditional button for the Navy was an anchor, often fouled with a rope. Spaceships don’t need anchors; they stay conveniently in their orbits till you unfurl the sails. So I went looking for either a sun button (because solar ships are pushed by the sun) or a compass (because Martian Imperial Navy officers specialize in navigation). Jackpot–I found these gorgeous ones. They cost way more than an anchor button, but I had to have them. Like Lucy, I felt some pain over the amount that this thing cost. Luckily, I did not have to sell any racehorses to afford it–I just did a little extra at my job.

The hat was from Etsy. Alas, I do not know how to make hats. The shoes were my second try for a proper pair. In the book, I gave Lucy “soft boots” to leave her feet flexible in zero-g. The thrift store did not have anything of the sort. So I got a pair that looked as much like period Hessian boots as possible, but they left me discontented. They didn’t look right with the breeches, and they weren’t the least bit flexible or comfortable. Finally, after much searching, I discovered jazz dancing boots. With a soft split sole and a sock-like fit, they’d be perfect for space.

My initial plan was just to make the costume, and then wear it to any occasion that I could get away with it. But when I happened to finish it before Balticon, I thought that would make the perfect debut. Didn’t they have a cosplay event? Some kind of costume party?

Well. It turned out what they had was an extremely competitive cosplay contest, which involved a stage and spotlights and theme music and a little routine. I hacked my presentation together the day of and spent that evening getting judged before the stage event. It was terrifying. Whatever the opposite of a theater kid is, is whatever I am. Plus I wasn’t even being anything anybody would have heard of.

As it happened, the judges both loved the idea of cosplaying my own character and were impressed by the work I had done. I got two ribbons, Best Workmanship and Best Presentation in the novice category. And the whole rest of the weekend, strangers kept saluting me. It was a nice feeling.

I guess I finally understand how Lucy feels about her uniform!